The Northern Naturalist #10

Common Loon, Five Loons, Review of Loon Lessons, and News and Notes, including a dark sky mystery, Coleridge-Taylor, and Taylor Coleridge.

Common Loon

The Common Loon (Gavia immer), the state bird of Minnesota, is an emblematic species of cold lakes, like the lakes in our area. Many people who are oblivious to other birds know loons, and if you spend time on a northern lake in the summer, they’re hard to miss. Their wailing yodel-like calls, and their astounding habit of diving in one place and turning up again far from the original spot always draw notice.

Common Loons are heavy, torpedo-like divers whose webbed feet are set well back on their body. Their feet have a flatter profile than other webbed feet, which provides for reduced drag when swimming. Loons do not use their wings underwater. An archaic name for loons in England was “diver,” so this species was called “Great Northern Diver,” until a recent checklist change. I miss the name “diver,” but I like “loon” too.

Because of the positioning of their feet, loons are ungainly on land and launch their bodies forward in lunges. The Birds of the World account says they “toboggan” their bodies when on land. If a loon lands on land, it’s a disaster, because they are stuck.

The structure and weight that makes them such great divers also means that they need a long runway on the surface of the water to take off. If they take off into a headwind, they can get into the air in as little as 30 yards, but without a headwind, on many small lakes, they need practically the entire lake to get going. If disturbed, they dive rather than taking flight.

Loons spend a fair amount of time swimming on the surface of the water, often “snorkeling,” with their head below the surface, watching for prey. They will often tuck one foot under a wing, showing off by cruising along propelled by one foot.

They can trap air in their feathers and compress them to expel the air to facilitate their diving. It seems as if they are underwater forever, but most dives are under two minutes.

Loons in flight have a noticeable “hunchback” appearance.

While they are best-known for their calls and diving, up close they are truly beautiful birds. An adult resting on the water has a slate-black head with a deep red eye. The white and black on the upperparts is crisp and sharply-defined. The black may have a greenish or bluish sheen in the right light. I have heard many people gasp a little when they first see a loon close-up through a spotting scope.

Loons moult out of this splashy plumage into a drab winter plumage. Then the birds appear mainly dark gray on the back and head with a white breast and variably smudgy-looking gray and white on the side of the head. One of the best field-marks for Common Loon in all plumages is the shape of the head—blocky and flat-topped, rather than a smooth arc like other loon species (see the article below for details.)

Common Loon adults have few natural predators. They are big birds, and few potential predators can dive to chase them. Bald Eagles are hypothetical predators, because there are frequent antagonistic interactions, but overt predation is not confirmed. (I might add cynically, Bald Eagles don’t overtly prey on anything—my impression of them is that they are mainly lazy scavengers, but this is, of course, not entirely true.) On the wintering waters, there are records of loons being taken by sharks. Many predators will take eggs and chicks.

When I used to assist my son, Lars Benson, with Road Scholar weeks in Ely, there was annual drama on the lake where we stayed. The lake hosted loon nests, and Bald Eagles nested in a broken-off white pine in the camp. Day after day, the eagles would harass the loons, the loons would sound the alarm, and some participants watched the interactions for hours.

Common Loons are especially known for their wild-sounding, varied vocalizations. Rather than give an inadequate description here, I will refer you to the many places online where you can hear their calls, for example, this youtube video on the Cornell channel (Common Loon audio).

While other loon species are strictly Arctic breeders, Common Loons are sub-arctic, breeding all across Canada south of the Arctic, with their range dipping south into just the most northern tier of states in the U.S. They are not considered threatened, and their numbers seem stable. Locally, access to the right kind of spot for their nests can be an issue, particularly on lakes ringed with cabins, where mown lawns and sand beaches may completely circle a lake.

If you want to see a loon closer, one trick you can use is to wave a white handkerchief when you see one across the water. For me, it has worked less than half the time, but it has worked on occasion; the bird will come over and take a look. This fits with my experience of Common Loons when I have been canoeing or boating in their presence. They are inquisitive and somewhat fearless. This is not true if they have chicks; if you do see chicks, they will likely ignore you, but stay away nonetheless.

Loons are piscivorous (fish-eating—it’s an unnecessarily arcane word to use in an article like this, but it’s fun to say). They eat many species of fish, and they prefer irregular swimmers that are easy to catch. In our area, this means perch and sunfish. They eat quite a few crayfish too. Where they winter, on the Gulf Coast, they still eat a lot of fish, but if needed, they’ll switch over to crabs and other crustaceans.

Long ago, while canoeing on Lake of the Isles in Minneapolis, we approached a tunnel that connects with an adjoining lake. Another canoe came out of the tunnel toward us. One of the friendly paddlers told us, “You’re in for a real treat—the channel in there is full of loons!” This was surprising news, and when we entered the tunnel, we were even more surprised to see maybe a dozen young Black-crowned Night Herons standing on the shore.

Which goes to show that Common Loons, at least in Minnesota, are in the general consciousness, along with Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons.

In the spring, Common Loons return to the inland northern lakes. Birds that don’t mate may go to the Great Lakes and form small flocks by mid-summer. Loons don’t nest on Lake Superior (nor I would guess, the other Great Lakes). The shoreline habitat is not weedy enough, and the wave action and changes in water level would make it unlikely. Common Loons are early and late migrants here. So long as there is open water, they get along just fine, whatever the weather.

I am writing about loons this time of year, because they linger, and it’s not unusual, when scanning the Lake, to see a single loon, the only sign of activity. Everyone else has left for the winter.

Five Loons

Common Loon (Gavia immer)

There are five species of loon on earth. Almost all sightings of loons in our region will be Common Loons. Your first question upon seeing a different-looking loon here should always be, “Why isn’t it a Common Loon?” Keep in mind that they molt and change appearance over time. The remaining four species are Arctic birds that wander into our region on rare occasions.

All winter loons are gray and white. This is the plumage we usually see in fall, and this is where the most confusion lies. If I could have found photos of all five loons in winter plumage (I only have Yellow-billed Loon below and Common in the preceding piece), this article would have been more helpful; but I hope it gives you some tips.

Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica)

On a worldwide scale, Pacific Loon is the most numerous loon. Here in the Northern U.S., they are regular (seen every year) but rare. For much of the history of scientific study of Pacific Loon, it has been considered the same species as Arctic Loon, and this has changed from time to time, so while current sources have it sorted out, one has to be careful when reading historic sources (anything before 1985.)

Winter Pacific Loons may have a dark “chinstraps” across their white necks, and if they do, that’s a clincher. Unfortunately, some do not, and some Arctics may have the suggestion of a chinstrap. When comparing winter loons, note that on Pacific Loons, the line between the gray and white on the side of the neck will be straight and clean. On Commons, it is irregular and sort of scalloped.

Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata)

When I was the naturalist at Hawk Ridge, two bird-banding brothers from Norway visited the Ridge for a week of hawk-watching. Someone found a Red-throated Loon on Lake Superior, and when I casually mentioned this to one of the brothers, he unleashed a mild, Norwegian epithet. Seeing my surprise, he explained that Red-throateds are exceedingly difficult to catch. The brothers voyaged out onto the ocean and used enormous, cumbersome nets to catch and band loons, but Red-throateds were so quick and dived so deep at the sight of a net that it was much more difficult to catch them than the other species. This fits with my experience here; they appear and vanish quite quickly, so now I think of them as The Wily Red-throated Loon.

Note that the lower part of the bill curves upward, and the top part of the bill is straight. Red-throateds often hold their bills above the horizontal, but it’s not a certainty, and other loons can do the same. Focus instead on the structure of the bill, and on the flatter shape of the head. Red-throateds often appear to have slimmer necks than Pacifics. Winter birds also have extensive white on the necks and face. Red-throated Loons are also regular but rare here.

Yellow-billed Loon (Gavia adamsii)

This is a rare Arctic species. I had been birding a long time before I saw one. I laughed out loud when I did, because I was so happy to see one, but also because in the past I had carefully scanned thousands of Common Loons to make sure they weren’t Yellow-billeds. I was looking for subtle differences, but when the day actually came, the differences didn’t seem subtle at all. The Yellow-billed was big and angular, and the pale bill color and shape jumped out. I guess the lesson is that if you see a loon that seems like it “sort-of, could be” a Yellow-billed, it’s a Common. Note the massive bill, with the lower part angling sharply upward. Also, the face is mostly white, and the faint spot on the side of the face can be a good mark, but it’s not always present.

Arctic Loon (Gavia arctica)

This one is an exceedingly rare visitor to our area. There is only one accepted record in our region, found by Ryan Brady at Herbster, Wisconsin in 2021. It’s tough to separate from Pacific Loon, so it’s possible some past records of Pacifics were actually Arctics, but we don’t know. Note the flat head and the flaring white on the flanks.

Loon Lessons: Uncommon Encounters with the Great Northern Diver, by James D. Paruk, University of Minnesota Press, 2021, 256 pp, $24.95 ISBN: 978-1517909406

Loon Lessons is by James Paruk, who has studied loons for over 30 years. The book is a compendium of what he knows about loons, along with the stories of his research and how he came to learn what he knows.

The book includes chapters on the structure of loons, courtship behavior, nesting behavior, vocalizations, behavior with chicks, other loon behavior, migration, winter ecology, conservation threats, and adapting to a changing world. The actual titles of the chapters are whimsical and reflect the effort that Paruk has made to entertain while presenting quite technical information.

That information is great. Paruk’s book is a worthy successor to Judith McIntyre’s The Common Loon: Spirit of the Northern Lakes, published in 1988. Both Paruk and McIntyre are among the six authors of the authoritative account in Birds of the World.

The book is written as a narrative, which works better for some sections than others. It also means that it could be a little hard to use as a reference. The index is good, but not exhaustive, so you might have to hunt around some to find particulars. It has a section of excellent photos in the middle.

As an example of Paruk’s style, he tells of a study done on predation of loons in Northern Wisconsin (Ch. 5, pp 68-70). In the process, he explains why loons prefer certain nest sights: they like islands, out of the prevailing wind, with a steep dropoff in the water next to the nest. The island sites reduce mammalian predators (especially raccoons.) The steep drop-off provides a quick getaway from an attacker (especially Bald Eagles).

If you like loons, I recommend reading this book. It will give you as complete a picture of the life of Common Loons as you will find.

News and Notes

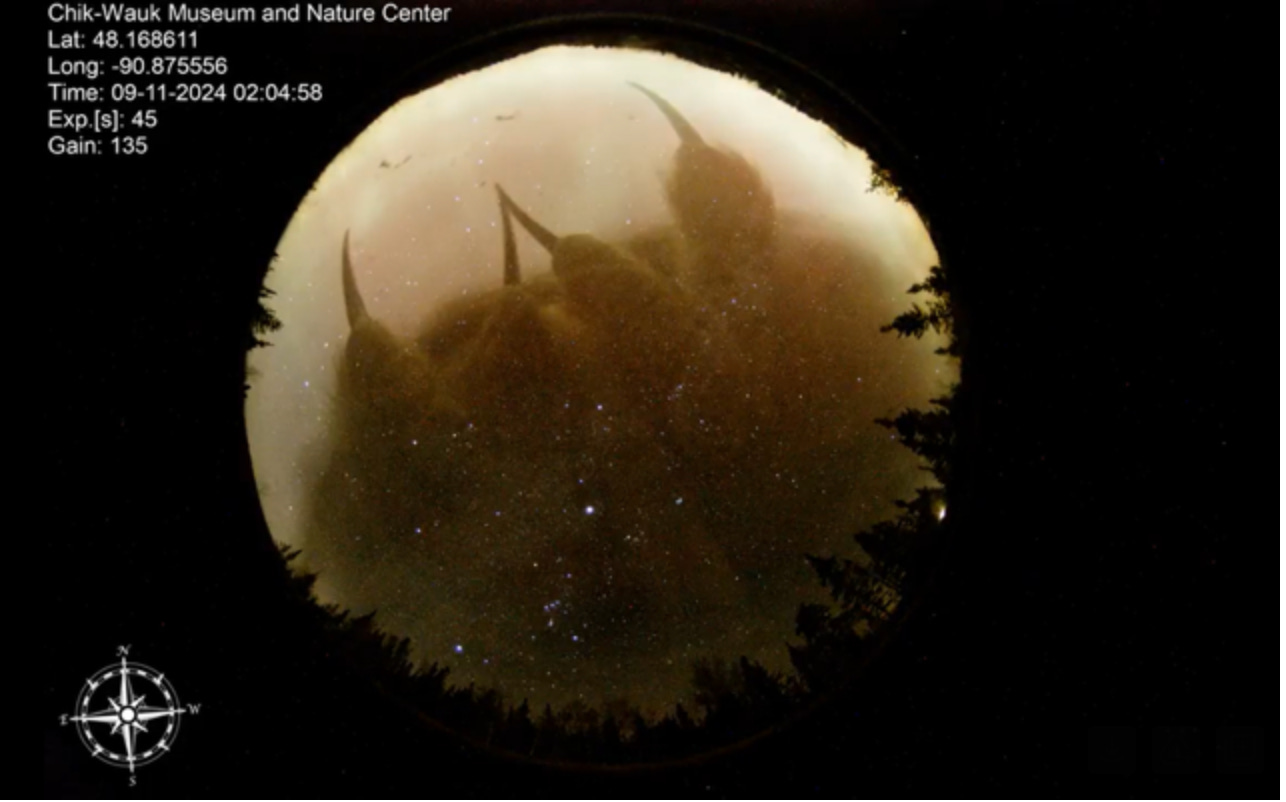

My friend, Sue Weber, sent this image from the dark sky camera at Chik-Wauk Museum near the end of the Gunflint Trail, which runs near the Canadian border in Northern Minnesota.

Chik-Wauk (Chik-Wauk Museum) is a charming museum and nature center. The main museum building is in the lodge of an old resort. Because the location is so remote from cities and towns, Alworth Planetarium (University of Minnesota-Duluth) has installed a dark sky camera on the roof of the museum. You can see a brief timelapse video of each night the next day at this link: Chik-Wauk Dark Sky Cam Sue says the camera often shows northern lights.

The image above is a bottom-up view of a Great Horned Owl perched atop the camera. It’s happened three times this month. When I first glanced at this image, I thought I was looking at a nest, with little beaks and feathers bunched together. Those of you who are practicing identifying owls by seeing the bottoms of their feet can use this image to practice!

By the lone sea shore,

Mournfully beat the waves,

Mournfully evermore,

The wild wind sobs and raves.

A sadness

And a sense of deep unrest

Brood on the clouds

And on the waters’ breast.

But lo! the white sea mew careering,

Float indolently by,

And lo! a snowy sail appearing

Gleams fair against the sky.

The sadness

And the loneliness depart,

And nature smiles

With sympathy of heart.

This poem, by Charles Mackay, a Scot who lived from 1814 to 1889, was set to music by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and printed in the program of a recent concert by the Twin Ports Choral Project. Mackay is most famous for having written Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, which some successful investors have credited for helping them thrive in the markets by avoiding delusions, and I suppose, madness.

I love the poem’s fitness for a November walk along the shore of Lake Superior, but I especially noticed the reference to “white mew” in the third stanza. It could be a reference to any gull, but most likely, it refers to the species formerly known as Mew Gull.

Mew Gull was split into Common Gull (the European species—likely the birds seen by Mackay) and Short-billed Gull (our bird, from Alaska and the Pacific Northwest), so I’m afraid its poetic career is over; no more “careering” or “indolently floating.” I have seen one Short-billed Gull in Minnesota, found in 1998 by Peder Svingen in Canal Park in Duluth.

The latest ebird/Clements taxonomy of bird species has been released. There are 11,145 species across 154 families. Kind of makes life lists in the hundreds feel small.

Since this issue has become all things loon, I’ll note that the word “loon” can also mean a lazy lout or an outright crazy person. The latter may be related to the word “lunatic,” suggesting the possible malign influence of the moon on one’s behavior. The image below is one of Gustave Dore’s illustrations of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (not Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the composer mentioned above, whose mother named him for this Coleridge, the author.)

The scene depicted here is from early in the poem, when the Ancient Mariner accosts a wedding guest, forcing him to listen to his surreal tale. He grabs the guest, who cries out, “Unhand me, grey-beard loon!”

And with that, I will unhand you for another two weeks! Thank you for reading!