Magpie Musings: Northern Naturalist #16

Black-billed Magpie; Magpies, La Gazza Ladra, and the Football Team of Newcastle upon Tyne; plus News and Notes

Black-billed Magpie

I made the loudest “Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch” noise that I could, and sure enough, a rough “chack-chack-chack” call came back. Soon a couple of Black-billed Magpies (Pica hudsonia) flew into a nearby aspen and looked down at me. Like their relatives, jays and crows, they are inquisitive, bold birds. They investigate humans and our activities. I can’t always lure them in like this, but often they find my odd calls too strange to resist, and they’ll come toward me for a better look. They themselves have a large repertoire of sounds.

Most people associate Black-billed Magpies with the Western United States and Canada. There, they are common birds. Everywhere they live, they are striking, attention-getting birds. I love seeing them on my trips out West, but I also love seeing them here in Minnesota, near the eastern edge of their range. They nest in the Sax Zim Bog north of Duluth, as well as at other spots in northern Minnesota.

The male and female plumages are similar and consistent throughout the year. The adults are black with contrasting white scapulars (shoulder areas), white wing patches and belly, and very long, dark tails. In the right light, the wings and tail shine blue-green, but the conditions have to be just right to see this iridescence. (Many of the photos I am including in this issue show some color; that’s a function of the photography, not the usual naked-eye view.) Young birds have less iridescence, slightly less white, and somewhat rounded tail feathers, but these differences are subtle.

Magpies are omnivores who eat mostly insects but will also eat seeds and carrion. They are apparently after maggots on carrion as much as the meat itself, although they do eat meat, including small birds (rarely) and snakes. They will steal meat from other predators, and they have been observed flipping cowpies to get at the bugs underneath. Out west, they will alight on elk, moose, and deer to eat ticks off their backs, but I have never seen them do this here.

In winter, when I am looking for them, I check farm areas with manure and spots with recent roadkills. Magpies used to follow bison herds and scavenge at gut piles left by native hunters; during that period, they likely had a much larger range. They moved into Minnesota after the 1920s, though “black desert” farming (corn and soybeans from hedgerow to hedgerow) has pushed the core of their range westward. There are records of many magpies being killed from eating various poisons, especially poisoned meat intended for coyotes.

They will cache (hide) food in winter. They use smell to find their caches, and probably as a result, most are used or abandoned within a day or two, because the smell fades.

Magpies will sit at the top of a tree near the nest and show off their white patches to claim territories. They defend their nest trees, but not large territories. Away from the nest, they often move, feed, and roost in groups. Most magpies mate for life. Their nests are large (two to three feet across) clumps of sticks lined with mud for the nest. The males bring in larger sticks, and the females do most of the interior construction. Once eggs are laid, the female is the exclusive incubator, and the male, the food finder for the female and young.

Miller and Brigham described a remarkable behavior among magpies—a “funeral” for a dead magpie. When a dead magpie is found, the finder begins calling. Other magpies (up to 40 birds) come over to perch nearby, calling loudly. Individuals then fly down one or two at a time, calling and walking around the body and pecking at its wings or tail. After ten or fifteen minutes, all the participants fly off silently. [Miller, W. R. and R. M. Brigham. (1988). "Ceremonial" gathering of Black-billed Magpies (Pica pica) after the sudden death of a conspecific. Murrelet 69:78-79].

There are magpie species around the world, with two species in North America. The Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nutalli) found only in California, is our other magpie. Magpies are considered non-migratory, though they are occasionally seen in places that are clearly away from the breeding areas, so they wander. I estimate that I see them about half the time I go birding in the bog (They aren’t really bog birds; they inhabit adjoining farmland and open forests.) It’s always a treat when our paths cross.

I learned some of the information for this piece in the fine article in Birds of the World, a great source of information for all species of birds (subscription service):

Trost, C. H. (2020). Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bkbmag1.01

Magpies, La Gazza Ladra, and the Football Team of Newcastle upon Tyne

Magpies are associated with Newcastle upon Tyne, in the north of England, because their football (American “soccer”) team are (American“is” lol) the Magpies.

Sports teams often go for the fierce and the strong: the Lions, the Eagles, or the Tigers.

This instinct is so strong that a team with a fine name like The Wolverhampton Wanderers most often goes by “The Wolves.” But Newcastle is/are The Magpies, apparently because in the early years, their black-and-white uniforms reminded some of magpies. The Magpies are a long-standing team, and I’m sorry to say that their glory days were from 1904 - 1909. They still have a lot of fans, in spite of their lack of recent success on the pitch.

I have never been to Newcastle, but I think of it fondly due to an experience I had as a young man. After graduating from college, I worked as a carpenter for some months, living at home and saving up my money for a trip to Europe. I flew to Glasgow and took the train to London. A friend from college was attending a women’s college there. She told me that she and her roommates could put me up in London, and suggested I stay long enough to catch some shows. So I planned to spend couple of nights at the college.

While my friend and her roommates were most welcoming, the college authorities would not have been, so the girls had to sneak me in and out. I called from a payphone when I got close to the school, and then they established lookouts at various spots, from the gate through the outer wall, down a passageway, up some stairs and down the hall to their room. They had four bunks, and I slept on the floor. They stood guard when I went to the bathroom. Leaving the college was equally complicated, but I wasn’t caught.

I had a sleeping bag packed, but I decided to use cheap hotels rather than hostels for the rest of my trip, so I asked if I could stow my bag there until I came back some months later. Off I went on my European adventure (much of which was with your proofreader and photographer, Pamela K. S. Benson), and I returned to London en route to Glasgow for my flight home. My friend had returned to the States, but her roomies were all still there.

The day I arrived in London in January was one of unrelenting, driving rain. It was my last morning for sightseeing, so I trudged around, wet and cold. When the time came to visit the college around noon, the trail of drips I left behind me should have given me away, but once again, I was not detected. When I got to the room, the girls invited me to stay indoors for a while to warm up and dry off. Besides, they were reading “Dracular” aloud and thought I might enjoy it.

Here’s where we return to Newcastle. The three roommates were all from Newcastle, which is famous for having a distinctive English dialect known as “Geordie,” which is also a nickname for a resident of the area. Geordie, I learned that day, is a most lovely-sounding dialect, but its great pronunciation differences from my own meant that I could not understand many words of the reading. It didn’t matter. I sat with my hot chocolate, transfixed by the exotic beauty of their reading, and faking my reactions by mimicking their reactions as appropriate. The vowel sounds seemed all different, and these girls had an expressive lilt as they read that kept me mesmerized all afternoon.

Since then, I have had a soft spot for Newcastle and the Geordies. When I came to know the real magpies of northern Minnesota, I discovered the team name, and occasionally, I check in on them online. A magpie species does live around Newcastle—Pica pica, the Eurasian Magpie, the same bird immortalized in Rossini’s opera La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie).

Which reminds me, one summer in high school, I played percussion in a youth orchestra. Before rehearsals and concerts, I and the other percussionist would plan through everything we were playing, laying out the triangle, the cymbals, the wood blocks, snare drums, various mallets, and whatever else. The overture to La Gazza Ladra has some good snare drum parts, and a couple of triangle solos. As it happened, I needed to play both, so I would finish my snare drum roll, grab the triangle dinger, and play my one-note solo.

When you play a triangle, you strike metal on metal, and you make a quick backstroke away from the triangle, so that it can ring freely. We were to do a concert outdoors, conducted by Henry Charles Smith, a world-famous trombonist, who was one of the conductors of the Minnesota Orchestra. We had a rehearsal indoors, for which my colleague had set up the instruments. When we got to the triangle solo, I finished my drum roll and looked for the triangle beater, only to find that it was not there. Yet the time had come, so I grabbed my wooden snare drum stick and whacked the triangle. As you can imagine, the sound was dull and not really what is called for on a triangle solo. The maestro stopped the orchestra and looked back at me with an expression of mixed annoyance and incredulity that someone could be this stupid. Since I was a kid and he was a nice man, however, he didn’t scold me, he just patiently, in simple language, and at length, explained to me why it was important to use a metal beater for a triangle and not hit it with a wooden stick that would produce no ringing tone.

When the day came for the actual outdoor concert, I didn’t rely on my unreliable partner. I brought my own blankety-blank dinger. When we got to the first solo (it comes back again in the piece), I dinged my triangle with gusto, and Henry Charles Smith beamed in my direction and continued conducting.

Unfortunately, in my zeal to play it loud and clear, I overdid the backstroke, and my triangle beater slipped out of my grip and flew into the bush behind me. One of my teachers was nearby, and the two of us struggled to extract the beater. But, you can see it coming, the next solo came around too fast, and all I could do was whack that triangle with my dull, wooden drumstick. Maestro Smith didn’t stop directing this time, but it was clear from the hurt and shock in his look in my direction that my thud had caused the scales to drop from his eyes, revealing that I must have done it intentionally. Why else would I play it so clearly the first time, and then malevolently ruin the second one? Now, when I hear this piece with “magpie” in the title, I remember that day; and I imagine that, for the rest of his life, upon hearing La Gazza Ladra, Henry Charles Smith may have thought of that moment, and of me, and asked himself, “What was with that kid with the triangle?”

Rossini’s opera, La Gazza Ladra, is known mainly for the overture that we played. One of the composer’s biographies says that Rossini was so far behind that the day before the premier, he was locked in a room until he finished, which he did (sort of like me and some issues of the Northern Naturalist!) The rather involved plot of the opera involves mayhem caused when a magpie steals various pieces of silverware and a coin. The characters of the opera blame each other, with disastrous consequences, until at the end, the goods are found in a magpie’s nest, and the opera ends happily.

The idea that magpies are attracted to shiny objects and would even steal them seems to have been common in European folklore. The notion was so prevalent that it has even been taken up for study by ornithologists, and it turns out that it’s not true. Magpies do not appear to have the slightest interest in shiny objects, nor do they steal them.

The prejudice likely got started, because magpies are indeed bold and inquisitive, as are all the members of the corvid family (crows, ravens, jays, and magpies). Magpies are so striking in appearance that even people who are oblivious to birds would notice them, and so the story began.

If I had real wit, I would have told Henry Charles Smith that a magpie stole my triangle dinger! Let’s go, Magpies!

News and Notes

We Probably Didn’t See Brad the Sheep After All

In issue #11, I wrote about seeing what I came to think was Brad the Sheep, a runaway who managed to return home over a long distance.

A friend told us that, in fact, there is a guy who owns goats in Knife River and runs around with them loose, so probably we didn’t see Brad the Sheep, but this guy and one of his goats. Apparently, there are sheep and goats running around everywhere! Another great story spoiled by an eyewitness.

Coals to Newcastle

“Like bringing coals to Newcastle” is probably the most famous reference to the city I mention above. It is well-known for its coal industry, whence the saying arose, and it is used to mock a useless action.

There is another such saying, from Greek, “Like bringing owls to Athens.” This is a reference to the owls who lived in the rafters of an early version of the Parthenon, and it means the same thing as the Newcastle saying.

They May Not Win the Big One, but They Are Developing a Fine Hobby

On the Minnesota Vikings YouTube channel Vikings’s safety Josh Metellus interviewed some of his teammates, asking them what was the strangest app they had on their phones. Quarterback Sam Darnold said that his choice would be Merlin, an app that identifies bird songs. Metellus replied that he had just bought a birdfeeder with a feedercam.

Big Year Update

I’m up to 52 species for my St Louis County, Minnesota Big Year (my quest to find as many species as possible in my home county in one calendar year—it’s a game to make me get out birding more, test my skills and knowledge, and have fun). Since the last issue I have added two species: Barrow’s Goldeneye and Horned Lark. My fruitless pursuit of a county Snowy Owl continues. People continue to see them a few hundred yards from our home, just across the harbor in a different state!

Barrow’s Goldeneye is a good one, not to be expected every year. Horned Lark is fun, because it’s a spring migrant. Nothing like hearing a sign of spring when the temperature is below zero!

I’ve settled on a goal for the year of 255 species. As I peruse the state checklist, that’s how many species I counted up that I expect are present every year. Many of those that I included or excluded could be debated. The total all-time list for St. Louis County is 414 species, but the best personal life list (Kim Eckert) is 352. My own county life list is 322. I’ll miss some of the expected species, but I’ll pick up some unexpected ones (like Barrow’s Goldeneye.) It will be a stretch.

Jim Lind completed a 2024 County Big Year in Lake County, the next county up the shore. I heard he finished at 247, which is tremendous. Lake County does have Lake Superior shoreline, but only rock beaches—no sand beaches; plus the rest of the county is more homogenous (boreal forest), smaller, and less-birded than St. Louis County. The total county list is 301, so Jim got 82 percent of the total list—that’s impressive.

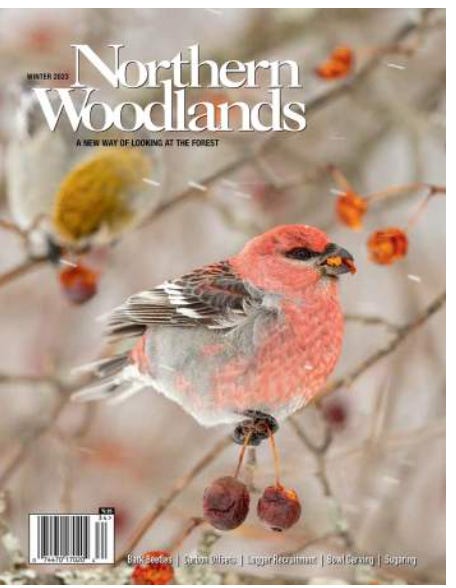

Northern Woodlands Magazine and the Center for Northern Woodlands Education

At around the time I was starting this newsletter, I came across Northern Woodlands magazine. It’s the publication of the Center for Northern Woodlands Education, located in Lyme, New Hampshire. Their mission is “to advance a culture of forest stewardship in the Northeast and to increase understanding of and appreciation for the natural wonders, economic productivity, and ecological integrity of the region’s forests.”

It’s a beautiful magazine, full of great nature photos and informative articles. Their focus is the woodlands of New England, and there’s a lot of information overlap with our forests. They also have a free newsletter. If you like this newsletter, I think you’d enjoy their publications.

St. Xenia of St. Petersburg lived entirely outdoors for 55 years, and she said this, “I have gotten used to the cold and rain, but I cannot get used to the bad weather in people’s hearts.”

I hope good weather prevails in your heart this month! Thanks for reading!

Hi Dave,

Mary and I saw magpies every day the year we lived in Umea, Sweden. They hang out with wagtails there.

John Pastor

Beautiful bird, I do not think I have ever seen a Magpie. Thanks for introducing me to it Dave.