Trees in Winter: Northern Naturalist #17

How Trees Survive Extreme Cold, Priming Your Brain to Learn About Nature, Review of Bird Books by Kenn Kaufman, plus News and Notes

How Do Trees Survive Extremely Cold Temperatures?

Some tree species grow all the way up to the treeline—the line north of which conditions are just too harsh for any tree species to survive. There aren’t many, but a few live on the edge by growing right up to the line. These are species we have here too, and it adds to my enjoyment of them to think of them growing in Alaska and Northern Canada too.

The northernmost of our tree species are Balsam Fir, White Spruce, Black Spruce, Jack Pine, Tamarack, Paper Birch, Quaking Aspen, and Balsam Poplar. (Alders and willows may also grow in the far north, but they are usually in shrub form there.)

Trees are particularly vulnerable to cold, because their stems and branches remain fully exposed to the winter weather. Many other plants die back to their underground parts, so the soil provides some insulation, plus whatever snow falls provides even more insulation.

All trees that are subjected to below-freezing temperatures have to have some way of getting through. Most tree species in our area are considered hardy, that is, they can make it down to -40° (F. or C.) Most species do this through supercooling. This means that the interiors of their cells are smooth, and there are no particles within the cells that could function as nuclei for ice formation. Ice and snow require something around which to form, be it a speck of dust. In our hardy species, the lack of these nuclei allows the cell to remain unfrozen well below normally freezing temperature.

However, below -40°, even these supercooled cells will burst, so the northern extent of these hardy species is limited to those that can make it below that temperature. How do the very hardy species do it?

They have the ability to squeeze liquid out of their cells into the spaces between the cells. The liquid will then freeze, but it won’t burst the cells and doesn’t hurt the tree. This is called intracellular freezing. Our eight very hardy species can do this, and it is reflected in their ranges.

There are other factors involved in the survival of individual trees, like exposure to sun and shelter from the wind; but the physiological response to absolute temperatures sets the foundation for surviving extreme cold.

Trees that can survive in the far north also have to be able to deal with short growing seasons and very poor soils. This is why there are more conifers than deciduous trees in this group. Because they don’t have to grow an entirely fresh set of leaves (needles) each year, they don’t need the heavy dose of sun and warmth that most deciduous trees need, since they must replace all of their leaves each and every year.

Start Priming Your Brain to Notice and Learn about Nature

Priming is prompting your mind to notice specific things that you might otherwise miss. Years ago, a friend of mine, Dennis Falk, asked me to lead a group of teenagers he was working with down a path along Tischer Creek in Duluth. We were to remain silent for the whole walk, and at the end of the hike, he asked the kids how many birds they had heard. Some said, “None.” Others had heard a few.

Then it was my turn; my number was in the upper twenties. The kids were baffled. Was it my exceptional hearing or my great skill that let me hear these birds? Neither one—it was priming. My experience told me what ways birds reveal their presence, but my brain was intent on discovering these tells, and not intent on thinking about much else, so I heard the birds.

Another example of the benefit of priming is the experience of looking for agates (a banded form of the stone, chalcedony—the Lake Superior region is famous for them). When polished and sliced, they are spectacular, but you don’t see that much when you are “picking agates.” You’re looking for reddish pebbles. They often turn up in the gravel spread on unpaved roads, so as you walk down a gravel road, you can sometimes find nice agates. Once you have done this a few times, your eye will get much better at picking them out. This also is due to priming—training your brain to see specific things.

I hadn’t thought of either of these situations as examples of priming before, but this winter, I am a student in Memory School with Mark Channon. Mark is a competitive memory champ, and he has years of experience teaching people how to improve their memories. This is a long-term interest of mine, and I have really enjoyed what I’ve learned so far.

One of the key lessons is that priming is among the most powerful ways of getting yourself to notice and remember certain things. Your brain craves meaning and seeks it out where it thinks it will be successful in finding it. If you are truly curious about something, your brain will help you learn about it. So, if you want to learn how to find agates, get going walking along a pebble beach or a gravel road and look hard. Because your brain has been primed to seek, it will be better at finding. If you just wander in the same place, without curiosity or without asking yourself a question, you’ll be less likely to succeed.

You can prime your brain for nature study in different ways, but asking yourself a question is the champion method. The obvious way is to ask yourself a question about what you hope or expect to see. This automatically makes a context for your brain to use to make meaning about whatever the subject is. You could ask, “What birds might be migrating north today?” Your brain will enjoy the context and the open loop of meaning and try to find answers for you.

Another way to frame it might be, “I think today I’ll see a Horned Lark and a Golden Eagle.” I made this question based on my knowledge that Horned Larks are often super-early migrants here, and that people have been seeing Golden Eagles this winter; so my brain will enjoy this hypothesis and keep my senses awake for finding these species.

The prior knowledge I have gives a little more context than just asking an open question, but the knowledge is not essential. Just ask yourself an open question that primes your brain to seek, like, “I wonder what my first bird will be on this walk?”

Birders do this kind of thing all the time. Many birding activities are simple games that prime you to look for birds as part of a contest; for example, my St. Louis County Big Year (update below). The locale and the time period are essentially arbitrary, but they add that little je ne sais rien to my birding. Could I just go out and listen and look around for birds? Sure, and I do; but the game adds a little bit of meaning and an occasion for priming myself to look.

Another kind of priming occurs during a Big Year or Big Day, when the members of a team talk about “what they still need.” “We’ve got all the corvids except Canada Jay—we could find that in the bog.” Now we’re primed to find it—of course, we often fail, but it’s not for lack of awareness. Even just listing random species that we’re not likely to see does prime the brain, but it’s not nearly as powerful as priming with some potential reality attached!

Many experienced birders have commented on a funny phenomenon related to finding new birds. Though you have sought a particular species without success for years, once you do find it, you are more likely to see it again within a shorter time period. Obviously, there are many factors involved in the presence of a bird in a particular place, but this phenomenon happens enough that birders have noticed it. I think priming is the reason. Once you’ve experienced the bird, and driven home the experience with the attendant excitement and maybe celebration, your brain is trained to seek it again.

Making guesses is another priming technique. You make a prediction, and your brain loves trying to find evidence one way of the other. Since I’ve been in Memory School, I have found a bunch of ways to incorporate priming into my life. It works.

Review of the Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America (Mariner Books, 2005) and the Kaufman Field Guide to Advanced Birding (Mariner Books, 2011—there are older versions; the first was published in 1990), both books are by Kenn Kaufman.

If you’re a beginner, this is my top recommendation for you, and frankly, it’s a good book for birders of any level of experience. It has one clear difference from most other field guides. Instead of delightful paintings or great photographs, Kaufman chose digital images and “photo-shopped” each to accentuate the critical fieldmarks needed for identification. The text, which is clear and correct, emphasizes the minimal knowledge necessary to make an identification in most circumstances.

This makes it the least confusing field guide, which is ideal for beginners. It doesn’t include as much detail about different plumages, etc. as the National Geographic and Sibley guides (my other favorites), and that’s a particular help when you’re starting out, although it can be a drawback in some circumstances.

Given that, it is still a solid field guide for all the regular birds of the U.S. and Canada. There are a number of guides which try to help beginners by selecting a limited number of species to represent, usually by choosing the most common birds. When I have worked in public roles with lots of visitors (as, for example, at Gooseberry Falls State Park), I have spent a fair amount of time explaining to people who bought a book labeled, “Birds of . . .” that most of the birds present were not included. When I visited a state park in Arizona, a park ranger threw down a copy of such a book on the counter and said, “This damn book doesn’t include all the birds!” So, I commend Kaufman for not going that route.

As noted, all of this makes it a fine book for beginners. Are there drawbacks? I can think of two. There will be situations where there’s not enough information. Ultimately, this is true of all bird books. There are limits to what can be included, and the Kaufman guide is on the skinny end of that spectrum. The other disadvantage is that the images aren’t especially attractive. You probably bought the book for the functional information, so that may not matter to you; but unlike quite a few other, gorgeous bird books, you’re not going to peruse it for beauty.

The Kaufman guide is also a handy way for intermediate birders to review. Before your Big Day or spring migration, spend an hour flipping through Kaufman to remind you of the most important field marks of the species you might see. The book includes a pictorial table of contents, which might help you find the right section of the book; and it has helpful front material about birding and how to begin birding.

The other Kaufman guide is literally intended for advanced birders. When it was first published, in 1990, it was a ground-breaking work, distilling Kenn Kaufman’s extensive experience and the published information about the frontiers of bird identification into a digestible and helpful guide. In those days, to get this kind of information (if you didn’t know it from first-hand experience), you had to dig it out of articles in journals and newsletters. Many other books about advanced identification issues have been published since, but I think Kaufman’s is the only one that is field-guide-sized and covers many groups of birds.

I learned so much from this book in the early years after its publication. It untied the knots of Empidonax flycatcher identification, changed the way I viewed sparrows, and helped clarify gulls and some other groups. Now there are advanced guides to quite a few bird groups, but this is still a great place to start as you move into more depth in your knowledge of identification issues. Along with a good regular field guide, I would say that this book is essential.

In an introductory note, Kaufman writes that his goal in the original Advanced Birding, as well as in the subsequent version, he sought to foster understanding of the birds, rather than just field marks. I think he succeeded. The only thing wrong with this guide is that he could have gone into more depth and length about various other groups, but then, of course, it would no longer have been a field guide.

Kaufman has expanded his approach to illustration to an entire series of nature guides. The only other one that I have used is the Kaufman Guide to Butterflies of North America, and it is just as helpful as the bird guides. I recommend both of the books reviewed here for early inclusion in your library of birding books.

News and Notes

Big Year Update

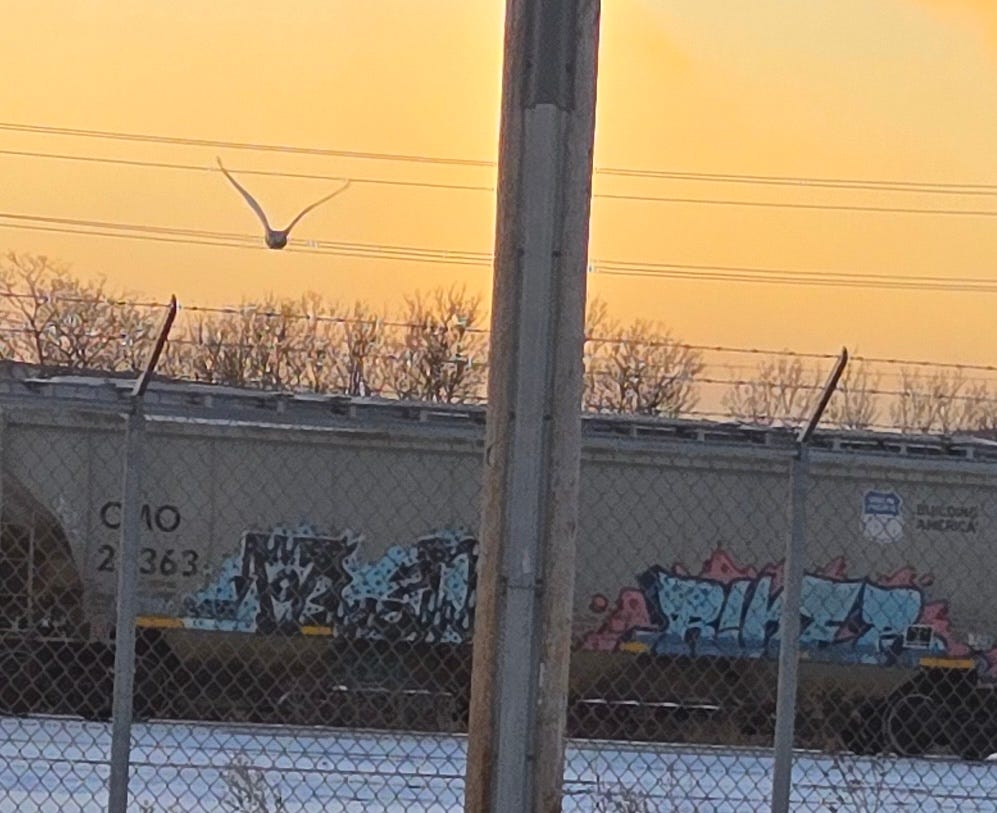

My St. Louis County Big Year is creeping along slowly, as is appropriate for this time of year. Subscriber Mike Hendrickson sent word that he had been regularly seeing two Snowy Owls in the Duluth Port Terminal. This gave me the resolve to go back one more time, and sure enough, I had a nice look at a female. You can see her in the picture below, flying off over the train cars.

Then, our son, Lars, and I spent a morning driving far north in the dark, seeking Spruce Grouse. In Lake County, we know several places that are likely to produce this species, but in St. Louis, I don’t have pinpointed spots. That was evident on this day, when we didn’t see any. In fact, for the first three hours we drove, we saw one bird, a Black-capped Chickadee.

We did, however, eventually get both Black-backed and American Three-toed Woodpeckers. The Three-toed, in particular, can be one of the most difficult regular species to find in Minnesota. We had great looks at both species. In addition, we had a brief look/listen at Pine Grosbeak, and I added American Robin and Mourning Dove for the year. A few days later, as we drove along the North Shore of Lake Superior, my wife, Pamela, spotted an eagle over the lake, which turned out to be a Golden. Golden Eagles are regular, but rare here, with a few dozen seen in late fall in most years. This winter, however, there have been sporadic sightings. This brought my total for the year to 59.

I went back to Ely, Minnesota on Valentine’s Day with Pamela. The Ely Winter Festival was in full swing. Among other activities, they have a Snow Sculpting Symposium. Among many creative sculptures, these were my favorites:

Given the weather we’ve had over the last week, I’d say it’s a safe bet that they haven’t melted yet. Thank you for reading, friend! I wish you enjoyment of the cold winter (if you’re somewhere cold), and the pleasure of thawing out, which will be here soon enough.

This was really interesting. I'm planning a visit to my local bird sanctuary in the coming weeks - and now I'm going to make sure I prime my brain before I go.

Dave- Awesome bits of knowledge given in just the right amount!! Thank you for putting this out and keeping me attached to the natural world and all it's wonder!