Golden-winged: Northern Naturalist #24

Golden-winged Warbler; Bird Surveys; Review of two warbler guides; plus News and Notes

Golden-winged Warbler

Wood warblers have been pouring back into their breeding grounds here over the past few weeks. They are all migratory, and the majority eat almost exclusively insects, so they can’t come back too early—the earliest, Yellow-rumped Warblers, have a more varied diet and can get by on seeds if they get caught in below-freezing temperatures. The others, though, have just been arriving.

One of the latest to return each year is the Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera). Each spring as I near the end of adding returning birds to my lists, I listen for their quiet BEE-buzz-buzz-buzz song. Once I hear it, I know that almost all of the 26 species of wood warblers we ordinarily find here will have arrived (or passed through).

Golden-wingeds nest in patches with dense shrubs, often adjacent to forest edges. They often appear in areas that have been logged relatively recently, where the shrubs have moved in enough to provide good cover. I often find them in Tag Alder (Alnus serrulata) swamps.

They are designated an endangered species, and their numbers have decreased in most parts of their breeding range in recent decades. Minnesota is an exception—the only part of their range where they are stable or increasing. This matches my experience with them—sometimes they are one of the most common birds on my Breeding Bird Survey (see below). They winter in mountainous, forested areas of Central America and northern South America.

There are several reasons why they may be decreasing generally. In some parts of their range, there is less logging and fire, and thus fewer acres of second-growth shrubby habitat. It was recognized that Golden-wings were increasing their range a hundred years ago, especially in New England, probably in response to increased logging activity. As logging has waned, so have the Golden-wingeds. In addition, at the margins of their territory, they face pressure from their close relative, the Blue-winged Warbler (Vermivora cyanoptera). Blue-wingeds sometimes compete for nesting sites, and hybridization can cause genetic dilution for Golden-wingeds. When Golden-wingeds and Blue-wingeds do hybridize, the two most common resulting forms are called Lawrence’s and Brewster’s Warblers; they are identifiable in the field. (See either of the books reviewed below for details.)

Golden-wingeds nest in loose cups of vegetation placed low in shrubs, just above the ground. The female builds the nest, and may build several partial nests if disturbed during construction. Once they start incubating, though, they stick with that nest. Like many songbirds, Golden-wingeds are subject to parasitization by Brown-headed Cowbirds, which lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. The precise extent of damage this causes for Golden-wings isn’t known, but it can’t be helping.

If you can catch a glimpse, they are an easy identification: a small, gray warbler with a golden cap, distinctive black-and-white facial pattern, and, believe-it-or-not, golden wing patches. They have sharply-pointed bills. It’s worth watching for the hybrid forms, and other than that, the only potential confusers might be Black-throated Gray Warbler, which has the same head pattern but lives far west of the Golden-winged range, or a chickadee, only because of the facial pattern.

As with many birds, catching their song is much easier than catching a glimpse of them. Early in the nesting season, males may sing from higher perches, but otherwise, they tend to stick within their shrubby homes. I think this is part of why I have always liked Golden-wings. Hearing their buzzy song reveals their secretive presence.

Bird Surveys

As I hit the trail to return down the Grand Portage to my car, I noticed something different out of the corner of my eye. Closer inspection revealed an enormous Black Bear. I looked at the bear; the bear was watching me. The hair stood up on the back of my neck. After a couple of minutes, lacking other options, I started slowly down the trail toward my car, several miles away. The bear decided to come with me, and walked through the woods alongside me, about 30 feet away. Occasionally, I stopped to see if he would (I’ll guess it was a male, because it was the largest Black Bear I had ever seen before or since). If I stopped, he stopped and waited. If I sped up, he sped up. We walked together like this the whole way back to the car, where I climbed in, bid the bear adieu, and drove back into town.

The reason I was on the trail that day was that I had been hired to do a breeding bird survey of the Grand Portage. It’s an 8.5-mile trail that was used by voyageurs—French-Canadian fur traders—to connect the Pigeon River with Lake Superior. There’s a national monument there today, and that’s who hired me to do the survey.

There are many different bird surveys in operation. They are often carried out by young birders who are piecing together several low-paying jobs to make a go of it. That’s what I was doing at this period in my life. From the time Kim Eckert took me along on my first owl survey, I did owl surveys, goshawk surveys, marshbird surveys, shorebird surveys, and others. The pay was not great, and it was strenuous work, but I loved doing them all, and they are fine memories.

There are also plenty of opportunities to volunteer to conduct bird surveys (along with frog surveys, butterfly surveys, and surveys of other groups.) Some surveys are short-term efforts. I once did a thrush survey that lasted three years. Others are longer-term, like the North American Breeding Bird Survey, which was initiated in 1966. I have surveyed a route in Aitkin County, Minnesota annually for about 30 years.

I need to conduct the survey on a day between early June and early July, when the weather conditions are favorable (i.e. light winds and little precipitation). On the chosen day, I get up at 3:15 am and drive to the start of my route by 4:50 am. At that time, I note the temperature and conditions and begin to listen. I listen for three minutes at each stop, every half mile along the route. There are 50 stops, and the survey takes about five hours.

These days, I usually do the route on my own, but my friend, John Heid, was a regular when he lived here, and my sons have helped too. Helping is not easy. It means holding the checklist and marking off each individual I call out during the three minute interval. That might not sound too bad, but I haven’t yet revealed that the mosquitoes are exceptionally intense along most of the route. It varies from year-to-year, but some years, I will wear a head-net and still come home with smeared blood and squashed mosquitoes on any exposed skin, along with some itchy mementos.

In addition to being willing to brave the mosquitoes, a surveyor needs to know all of the songs of all the birds that could turn up on the route. There are trainings available to get you there. Each state has a coordinator who finds people to cover the routes. The survey is jointly managed by United States Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service.

The great thing about doing a survey is that it gets you out to listen to the birds and disciplines your observations. You just go to where you’re required to go and find out what’s there. You’re not selecting hot spots or chasing rarities. You just go and do the survey. This reveals different aspects of the bird life in that area. You learn what’s common, what’s widespread, and after some years, how rare certain birds really are.

I love my route in north-central Minnesota. It’s within a band of territory that extends from the Eastern border across the state to the prairie that holds the greatest diversity of bird life anywhere in North America north of the Tropics. Most survey routes across the continent turn up 30 or 40 species. I get 80 almost every year, and I have had over 100. It’s all good data, but the variety on my route makes it more interesting.

It has also been interesting to see how the landscape has changed. Along my route, there are more human habitations than when I started, and many of the open areas have grown up; so the sedge meadow where I used to get multiple Sedge Wrens is no more, for example.

By doing a survey every year, I am guaranteed to put my “bird-ear” through its paces at least once a year. Plus, there are always gifts along the way: calla lillies blooming in the ditch, fishers dashing across the road, butterflies once the sun is up and warming things, and many others.

One of my favorite bird survey experiences happened when I was doing an owl survey along the Gunflint Trail, a roadway that runs near the Canadian Border from Grand Marais well up into the Superior National Forest. After supper in Grand Marais, I drove up to where my survey began and waited for the appropriate time after sunset to begin.

It was a glorious evening. The woodcocks were displaying, snipes were winnowing overhead, and lots of early spring birdsong had begun. Once it got really dark, I could begin listening for owls. I think my stop intervals were ten minutes for that survey, and I enjoyed the quiet time in the woods after dark. It was a moonless night, and the stars were great. At some point along the way, I began to notice some northern lights, which is always a treat. The lights kept increasing, and before I was done with my survey, they filled the sky. They got so strong that the ambient light from the aurora actually increased as a result. At one point, it got so bright, that the woodcocks started displaying again! It was a moment I will never forget, and another experience that made me glad I was doing a bird survey.

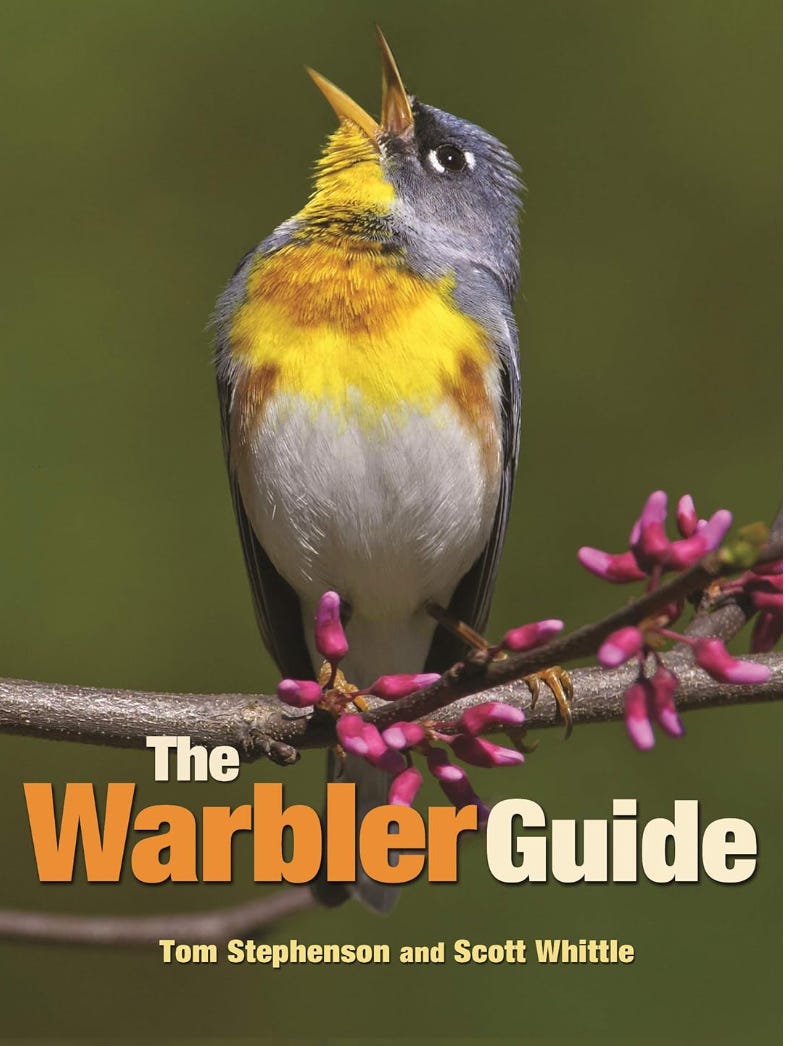

Review of The Warbler Guide, by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle (Princeton, 2013); and A Peterson Field Guide to North American Warblers, by Jon Dunn and Kimball Garrett with illustrations by Thomas Schultz (Mariner Books, 1997)

There are two excellent books about North American Wood Warblers. The Peterson Field Guide to North American Warblers, by Jon Dunn, Kimball Garrett, Thomas Schultz, and Cindy House came out in 1997, and it was an early in-depth treatment of a species group. I loved it when it came out, and I still enjoy picking it up and reading a little sometimes. The accounts, created by true experts, are full of interesting, pertinent information about each species.

The second, The Warbler Guide, by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle, came out 16 years later. It was a revelation then, and it continues to delight me whenever I consult it. It is a comprehensive, photographic, identification guide. That’s it—not nearly so much natural history information as the Peterson guide, except when the information will help with identification. For species with strongly different plumage forms, there are separate species accounts. For example, for American Redstart, there’s an account for “Adult Male” and another for “Female, First Year Male.” (The female and young males appear similar.) These accounts are in alphabetical order (the accounts for the same species are kept together.) The book contains sonograms and descriptions of songs, plus range maps and graphs showing the season of likely occurrence. There is a quiz section at the end.

There are “quick finder” charts that show all of the warblers from, for example, the side, or the face, or the undertail coverts. There is an accompanying app, which incorporates the guide’s information, and which allows you to rotate photographic models of the birds in 3D. It’s undeniably cool, although I have not used that feature as much as I thought I would when I first got it.

Both of these books are too large to easily carry into the field, and that’s just fine. When you’re birding, you should be looking at the birds, not the books; so they are reference books, not field guides. Both are authoritative and a pleasure to read, and both are well worth adding to your library of bird books.

The Peterson Guide has relatively few photos but includes beautiful, illustrated plates. The advantage of painted illustrations over photos is that a skillful artist can subtly emphasize the things you should be looking for and generalize different light conditions and views into one painting. Photos are always one instant in time, so the view and the individual bird might be a little misleading. The Warbler Guide only has photos, but it avoids much of the downside of photos by the amazing number of photos for each species group.

If you live and bird in the temperate East of North America, or anywhere where there are lots of wood warblers, I recommend both of these books.

News and Notes

The migration jumbles birds together. Once they have sorted into their breeding territories, they will only have to deal with those species that share their haunts. On mornings here when lots of birds are passing through, all sorts of uproar and alarm-calling breaks out. A calling Merlin elicited several alarms the other evening, including that of an American Robin that kept at it for a surprisingly long time.

My St. Louis County Big Year continues to languish under the weight of a lot of work and busyness. I have missed a ton of splendid discoveries made by the industrious birders here. I did get a welcome Blackpoll Warbler at Bending Birches garden center, where we were picking up bedding plants. Blackpolls nest further north in Canada, so here one needs to get it during migration.

Another nice sighting was the Northern Harrier that flew low through our back yard, ten feet from where I sat on the patio. It was a beautiful gray male.

A Gray Catbird has returned to the yard, and I have a guess as to where it’s nesting, in a patch of shrubby woods just down the street.

We had a great trip to the Indiana Dunes Birding Festival. It was a pleasure to make new friends, and to encounter some old friends, some of whom I had guided in the past. The festival was packed with things to do, and it’s a great birding area. The highlights of the many birds we saw were, for me, a singing Prothonotary Warbler, great looks at Willow Flycatcher, and a lifer Red-shouldered Hawk nest.

This is the time of year when the birds come to us. Even if we can’t make special trips often, we can enjoy the birds anywhere, because now they are all over the place!

Wishing you lots of spring bird song! Thanks for reading!

What a singular experience -- to see the woodcocks start to display in the brightness of the northern lights!