The Northern Naturalist #1

Gray Catbird, Learning Bird Song, Review of The Breeding Birds of Minnesota, News and Notes

Gray Catbird

Photo by Pamela K. S. Benson

The sharp, twitchy song of a Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) is animating my backyard these days. I think a pair is nesting just beyond the fence in a full lilac hedge. Catbirds are common but often missed. While they’re on the breeding grounds (around here, May through August), they skulk and seem reluctant to fly out in the open.

When one does catch a glimpse, it’s usually when they’re making a quick dash from one brushy patch to another. So it’s a particular pleasure to have them hanging around the backyard, where I can see them.

Gray catbirds are gray (imagine that!)—most of the body is slate gray, but they have a black crown and black tails. The eyes and legs are black. The most striking feature is a rich chestnut color under the tail, but this is often hard to see. So, at a distance, a catbird is not very distinctive.

They are much more apparent from their song. Their name comes from a mewing, usually repeated three or four times, that is cat-like enough, but probably won’t fool you into thinking it’s a cat. On the other hand, the bird’s name references “cat” in many languages, so maybe it would fool you. My favorite non-English name is the French Moquer Chat (cat mocker).

The mewing often precedes, or is included within, a long song of jumbled vocalizations. These can go on for several minutes, often with brief pauses between the phrases.

Catbirds are in the bird family mimidae, which also includes thrashers and mockingbirds. (There is one other catbird, the Black Catbird, which is a Mexican and Central American species.) All of these “mimics,” sing long, complicated, variable songs, and all include the mimicking of other species in their songs.

Catbirds, however, use less actual mimicking than the other mimics do. In fact, much of their singing is creatively original. Analyses of Catbirds songs have counted over 100 original phrases in one stretch of song. A catbird can use both sides of its syrinx (bird’s vocal organ) to create sound, so they can produce two different sounds at once.

If you’re trying to distinguish a Catbird sound from the other mimics, note that the shorter phrases don’t repeat. Brown Thrashers double their phrases, and Northern Mockingbirds will often repeat phrases three or four times, as well as returning to similar, trilling notes within one song period. Other mimics could probably reproduce the catbird’s mewing, but I’ve never noticed it.

I’ve noticed that my male catbird (the sexes are barely distinguishable by sight, but females sing less and more softly, so I’m guessing this is the male) often mews and then sings before coming in to snatch one of the grapes (halved) that I put out for them. It’s possible that the mewing serves to clear out other species before the catbird goes to the food, but that’s conjecture. The singing of mimics has been studied a lot, and some possible functions (mostly the idea that males are competing with their songs) have been ruled out, but not much has been conclusively discovered.

Catbirds have long tails in relation to their body and wing lengths, and to my eye, in flight it looks as if they’re dragging that big old tail along. They flick their tails and wings in courtship, and my catbirds flick their tails when they’re collecting fruit.

Along with fruit, they eat a wide range of insects. The young are fed mostly insects. The fruit-eating helps them if they’re caught in early or late cold weather during migration, but they are neotropical migrants, so their migration is timed by changing light and not by weather. Unlike some other fruit-eaters, they don’t come north early when the weather is warmer.

They give the impression of climbing through the bushes sometimes, and I assume this is when they are gleaning for insects. In migration, they have often been seen catching insects in flight, but I haven’t seen that much here.

Catbirds have been moved around the taxonomic scheme a few times. They have similarities to certain other groups: the complicated song and skulking of wrens, the reedy notes and size of thrushes; but genetically, they aren’t closely related.

Wherever they live, they like shrubby, scrubby habitat, often near water. They prefer deciduous shrubs for nesting but will use coniferous shrubs too. They are one of a handful of songbirds that recognizes cowbird eggs in their nests, and they roll them out so their own brood is more likely to survive.

Listen for the mewing, and watch for the tail-dragging dash from one bush to another, and when you get the chance, enjoy the fine sight of a Gray Catbird.

Photo by Wen Zhu on Unsplash

Beginning to Learn Bird Songs

Among the pleasures of experiencing the outdoors, listening to bird songs is my favorite. I long for the singing season (April to August in my part of the world), and even though I immerse myself in song during that period, I will miss it when it’s gone.

Learning bird songs is also a big advantage if you’re a birder. If you can identify a bird by it’s song, you can find it behind trees and other objects, anywhere around you including behind you, and in the distance.

I expect to be writing more about bird songs, but this short post can help you get started or move along your path to knowing the birds through song:

The best way to associate sounds with the species that made them is to catch the bird in the act. Once you’ve seen a bird in the act of singing as you are hearing it’s song, you’re likely to remember it. The problem with this is its rarity. I have probably seen and heard the majority of our songbirds singing, but it has taken me decades.

Next best is to learn from another experienced birder. It’s so much quicker to have someone point out the song and identify it for you than any other method. Experienced birders can also steer you off your mistakes and articulate the aspects of a particular song you’re looking for. If you have access to experienced birders, great; if not, obviously this won’t work.

Beyond these options, you’ll need to pick your way through the soundscape, seeing the singers when you can, going on guided field trips when you can get to them, and using resources like the following:

The Merlin song identification app. I haven’t really used this app, but I have friends who use it and think that it has been helpful in learning song. On the few occasions when I have been around when someone was using Merlin, it was wrong at least some of the time. I’m sure it’s always being improved, but even if the basis is refined, I can imagine that it’s a particular difficulty to pick out one song when several are in the air. You might find it useful.

You could also try Nathan Pieplow’s books, The Peterson Field Guide to Bird Songs of Eastern North America, and The Peterson Field Guide to Bird Songs of Western North America. You will need to take some time to learn how to use the apparatus in the books; they are full of interesting information about the multiple songs of birds.

Your field guide is another good source of information. All of them have descriptions of songs, and the Sibley Guide to Birds, by David Sibley is considered particularly strong on song.

The important thing is to get started. It takes time. When I began learning bird song, for about the first five years, I felt like I was starting over each year, but thereafter, it seemed to stick. Now I might hesitate when I hear a song for the first time each year, but it comes back quickly, and then I’ve got it.

I fear this is more daunting than encouraging, but all I can say is that it is entirely worth the effort!

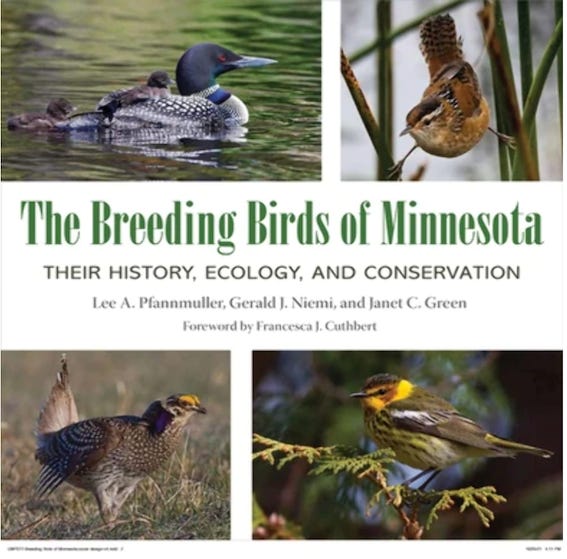

The Breeding Birds of Minnesota: History, Ecology, and Conservation, by Lee A. Pfannmuller, Gerald J. Niemi, and Janet C. Green, University of Minnesota Press, 2024. ISBN 978-1-5179-0679-5 $59.95 (US) hardcover

The publication of the The Breeding Birds of Minnesota: History, Ecology, and Conservation marks the conclusion of sixteen years of work on the project of cataloguing the bird species that nest in Minnesota. It was a gargantuan task. Minnesota has a diverse bird life. It lies at the meeting of four biomes: boreal forest, prairie grasslands, deciduous hardwoods, and aspen parklands, so it has birds from all four. Add in its large size and the presence of a Great Lake and the Mississippi River and associated streams, and you’re talking lots of birds.

The effort culminated in the publication of the results online in 2017 (https://mnbirdatlas.org/). This year, that data was condensed and published as a book. (I participated in the project as a volunteer surveyor in the Sax Zim Bog north of Duluth, and I know two of the authors.)

It is an impressive book. At first glance (or lift) you would think it was a coffee table book, and maybe that is part of the intent. It weighs over eight pounds, and the cover measures over 11 by 11 inches. When I first opened it and began paging, I tore a page right away—it’s a heavy page, and I should have been more careful, but the paper isn’t quite up to the task. I don’t have an open shelf that will accommodate it vertically, so it will lie flat with my copy of Minnesota’s Natural Heritage.

The data is laid out clearly and supported by helpful maps, graphs, and illustrations; and the text is clear and economical. The species accounts begin with helpful reviews of the historical accounts (Birds of Minnesota by Thomas S. Roberts and subsequent book-length reports of the distribution of birds by Janet Green and Bob Janssen). I was pleasantly surprised at the extent of the species accounts, which include a lot of detail about identification, life history, abundance, and more.

The atlas project was complex, to say the least. It used a solid protocol to collect the data, and then used modeling to try to account for some of the vagaries of trying to get at so many birds in such a large area. An effort like this produces a lot of information of great interest, but it is one depiction of our bird life and must necessarily include caveats. The authors articulate some of these issues; and for the vast majority of the 250 species treated, the estimates are close to other surveys and past estimates, and the potential areas of major inaccuracy are rare. The book contains detailed discussion of the methodology.

The species accounts and some of the ancillary material treat conservation efforts and needs. The strength of this project and book is the detailed view of bird status in one four year period in the recent past. That core part of the book is immensely interesting on its own, and it will be of great value in assessing the future status of the birds of Minnesota.

The predictions of the effect of climate change are different. It appears that these predictions all come from one source—a National Audubon Society report. The book includes a chart based on that report showing which Minnesota birds will be extirpated in different temperature-rise scenarios. To point out but one telling problem with this, the predictions for the species included are all negative. There are no situations, apparently, where some level of warming might bring us new species from the south, or increase any of our current species. This is not up to the high standards of the rest of the book.

Whatever the future brings, this project and book have established a baseline to measure from, and, in the meantime, a treasury of information that can be studied and used for other research. This is a beautiful book; I have already profited from it, and I expect to consult it often.

Photo of Carolina Wren by Ryk Naves on Unsplash

Northern Naturalist Notes:

This section of the newsletter will include brief notes of varied interest: interesting sightings, relevant research, my comments and musings, and things to look for outdoors over the following two weeks:

Our state flower, the Showy Lady-slipper (Cypripedium reginae) has been blooming over the past week or so. It is most abundant in the north central part of Minnesota, but there are patches at Gooseberry Falls (near Ladyslipper Lodge) and Jay Cooke (west of the office building) State Parks, as well as along Hwy 29 northeast of Floodwood, Minnesota, and no doubt, many other places.

Photo by Alexandria Szakacs on Unsplash

We’re looking at a forecast of a string of hot days (in the eighties F. is hot for us), so the plant-life will continue to roll forward with the season. The roadsides are lined with Orange Hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum) and Birdsfoot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus). Strawberries, Juneberries, and Dewberries are ripe. Coral Fungus should be fruiting soon.

The first fall migrants have arrived—shorebirds who have already left their Arctic breeding grounds to make the long journey south. A few have shown up on the sand beach of Minnesota Point on Lake Superior in Duluth. Even though I have been aware of this for a long time, it still shocks me to think that fall migration has begun as early as late June!

Another seasonal area where I am out of sync is in what the solstice means about the summer. For me, and I suspect for many, the solstice feels like an early-summer event. Of course it is the quintessential MID-summer event, and for flora and fauna, it is the pinnacle of solar and biological energy. It’s all downhill after the solstice, now almost three weeks ago.

Yesterday I saw a starling chasing a pigeon, full-tilt. What on earth had that pigeon done to deserve that? Lots of smaller birds chase larger birds, but I had never seen these species do this before!

Thanks for scrolling this far! So far, so good, and I know I will improve this newsletter with practice. Please share it with your friends, and let me know in the comments how you think I can improve it and what you’d like to see in the future!

Dave, I enjoyed reading this and look forward to more!

Excellent newsletter, Dave! It was fun to read more in-depth information about the gray catbird. It appears that our backyard is an ideal nesting area for them, and we do see (and hear!) many. I absolutely loved your commentary on bird songs! Yes, please do more of this in future publications! The section inspired me to find my old CD of the Peterson Field Guide for Eastern/Central Bird Songs. But there's nothing like going with an experienced birder to train the ears to identify the songs. Fortunately, we know one such person! Thanks also for the Review. We're building our library and it's good to have some guidance on this. Overall, an outstanding first edition! Thank you!